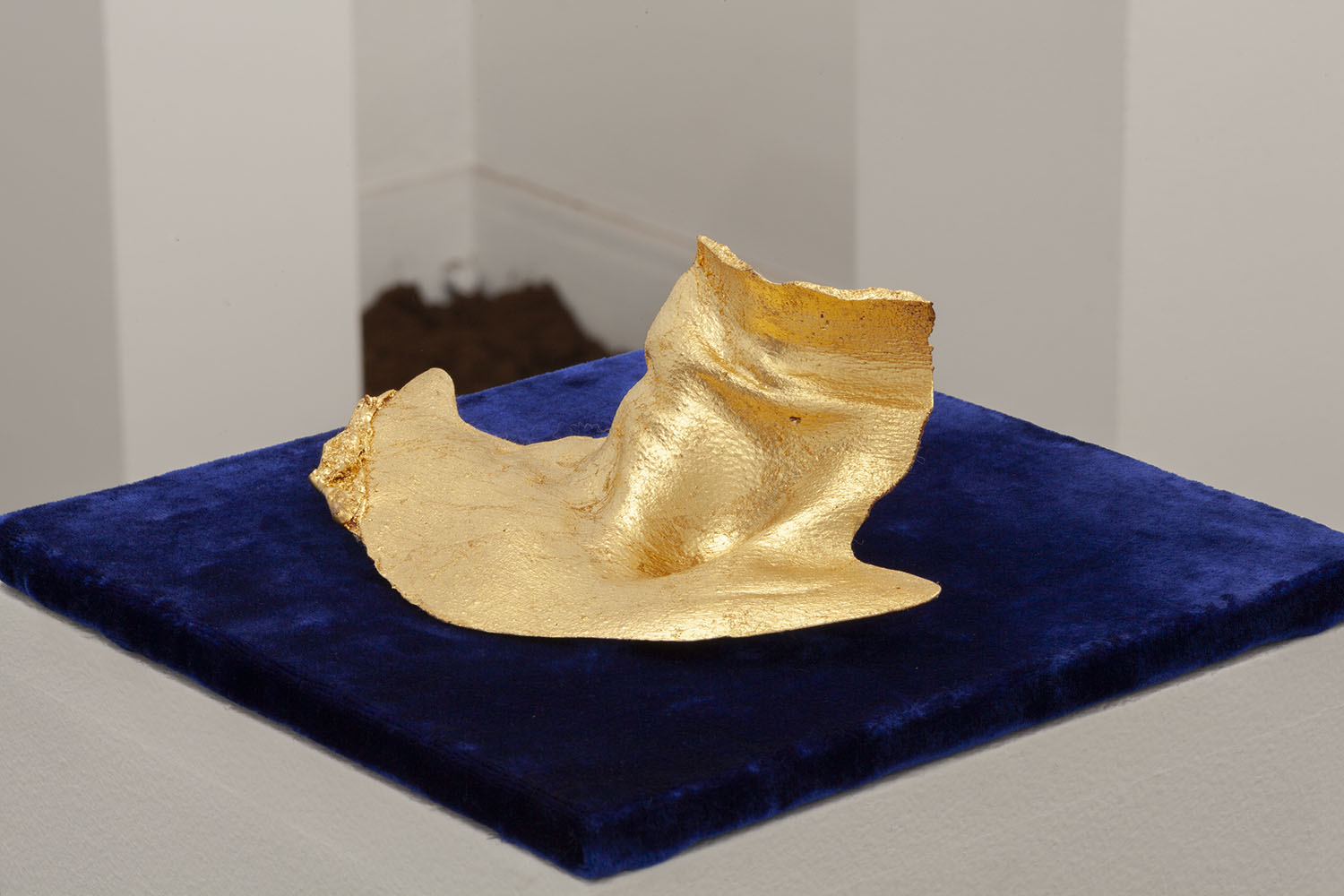

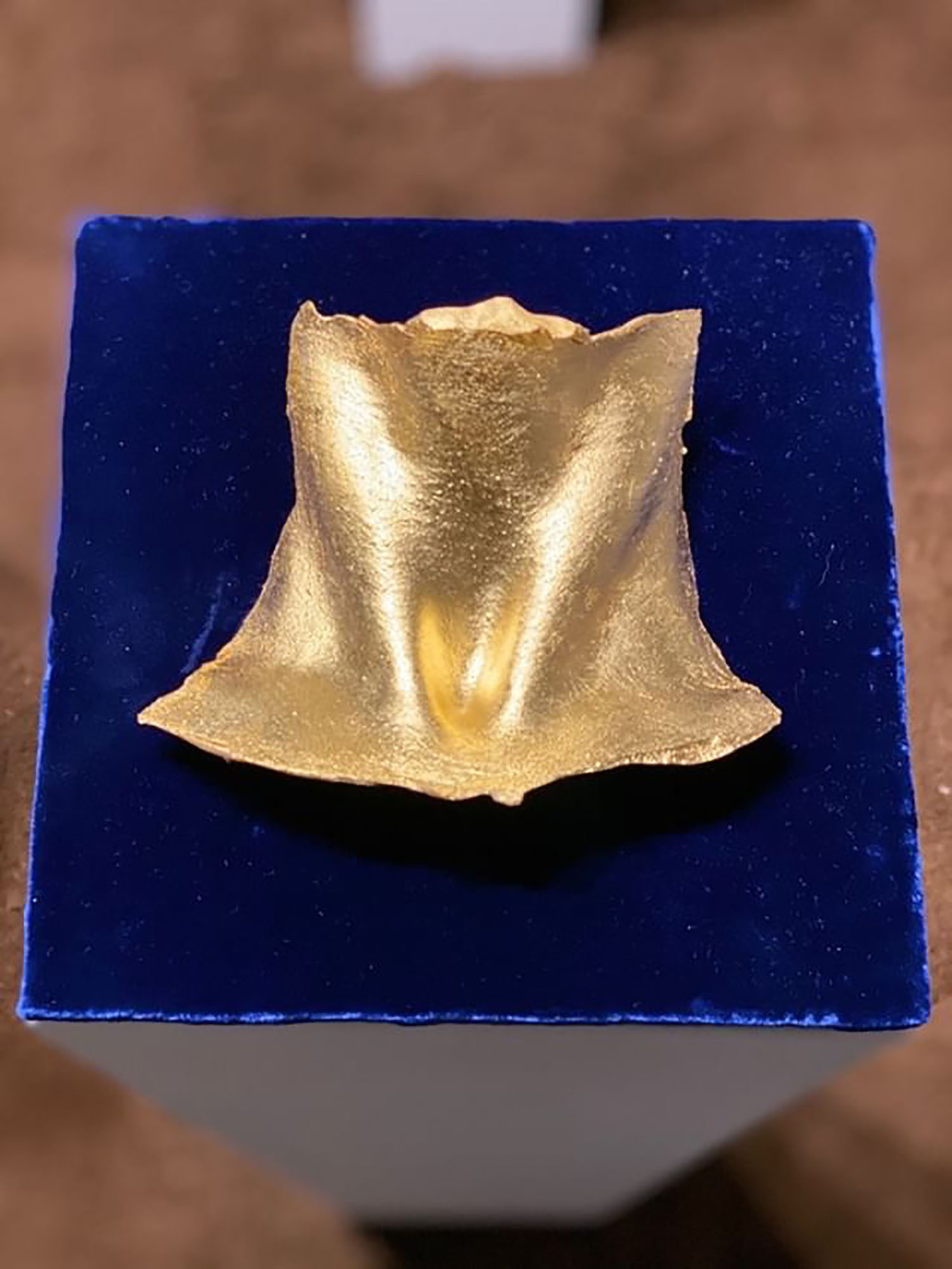

The Second Coming of Fatima | Installation, gypsum, gold leaf, velvet, powdered mica, dirt, 2019

The Koh-i-Noor, or Mountain of Light, is one of the most storied gems in the world. Originally sourced from the Golconda mines of Andhra Pradesh in the 18th century, the diamond now rests amongst the British Crown Jewels, after passing through several bloodied hands and developing the reputation of bringing ill fate to the men who possessed it. Lore that grew up around its misfortune says that it is meant to be worn only by gods and women. Fifty years after British lawyer Cyril Radcliffe’s midnight drawing of an arbitrary line split the subcontinent in two – an ill-informed cartographic gesture that resulted in large scale violence, mass rape, a mortality toll of 2 million and the displacement of 14 million – both India and Pakistan continue to request the repatriation of this jewel, amongst other stolen artifacts.

Artist Arshia Haq, whose work considers this history and the many centuries of violence that led to its manifestation, centers the embodiment of mourning as a way to reconstruct her and her collective relationship to pain, loss, and violence. Women, in particular, were brutally objectified in the pursuit and desire for nationalism upon colonialism. Anthropologist Veena Das writes that, “the violence of the Partition was about inscribing desires on the bodies of women in a manner that we have not yet understood. In the mythic imagination in India, victory or defeat in war was ultimately inscribed on the bodies of women.” Haq harnesses the affect of this historical trauma and creates a room for reflection. The result is a haunting installation, The Second Coming of Fatima, that speaks to the complex interplay between the validation and erasure of women, specifically within the context of conflict. Fatima, the only daughter of the prophet Muhammad, is an iconic figure in the Muslim female pantheon, and is often invoked in prayers of protection and healing. In a room covered with earth lies an arsenal of gilded throats, the jewels which are also the vessels of severed or silenced speech. Sitting on pedestals, the pieces are fragments of the violated body worthy of reverence, an homage to the physical costs of the colonial acquisition and appropriation of women’s jewelry, wealth, and worth in the Indian subcontinent. Acquisition, on an intimate and institutional level, is explored here through the lack of repatriation of collection objects in Western museums and the violation of female intimacy, rites, and rights.

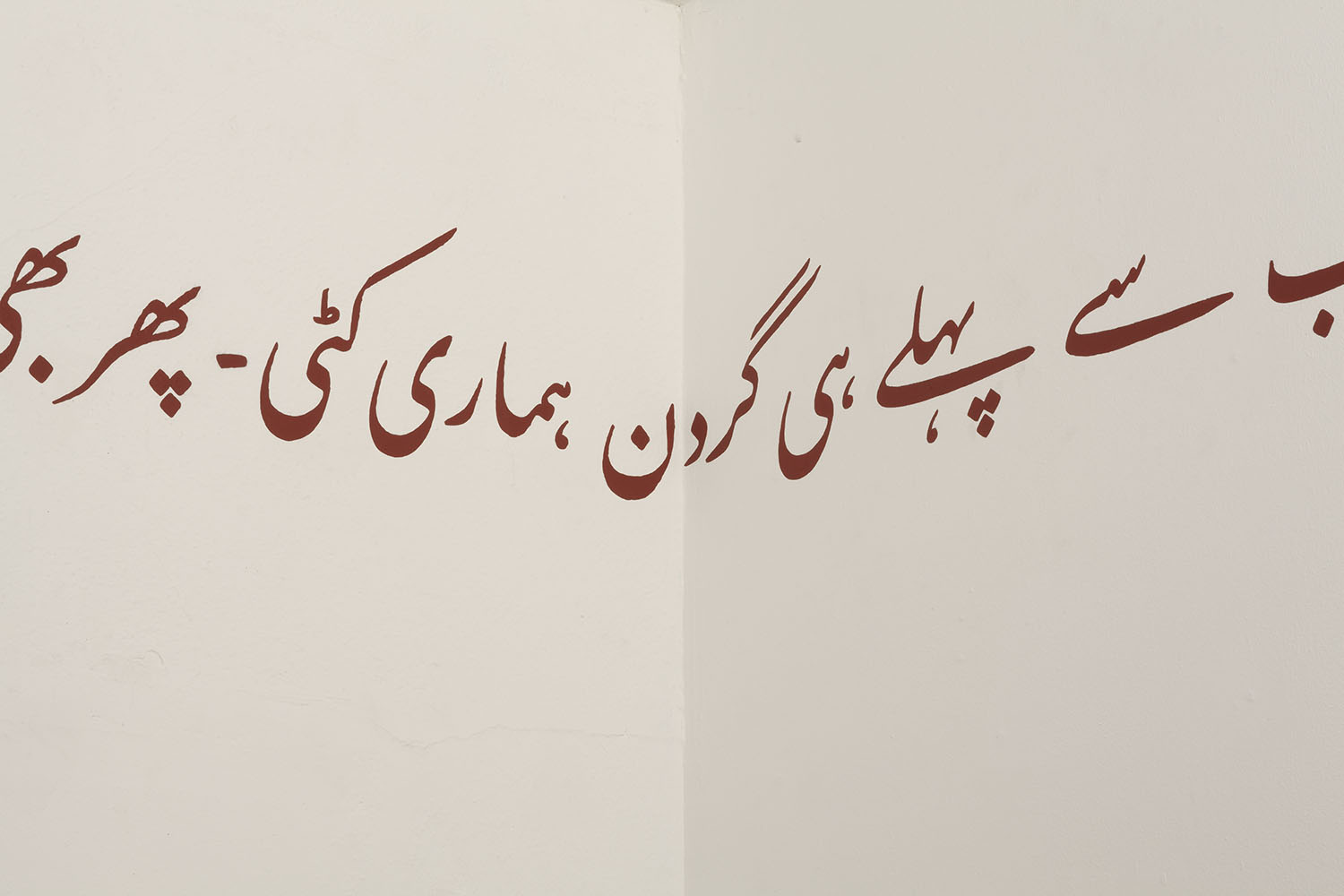

A sound piece made in collaboration with artist Nour Mobarak merges a sonic rendition of the above Urdu poem with field sounds, from bird songs of the Deccan plateau to news broadcasts as well as more guttural evocations. Haq’s installation pays homage to historical, religious, and mythical female characters, through which she gives form to the amorphous and nebulous process of mourning. Loss erupts from within the earthen soil, and grieving those sacrificed becomes a release, a catharsis that seeks to heal. As Das writes, “could that which died be named, acknowledged, and mourned?”

When the land of flowers required blood, Our throats were the first to be cut Still, the owners of the garden say, This land is ours, and not yours. |

The Koh-i-Noor, or Mountain of Light, is one of the most storied gems in the world. Originally sourced from the Golconda mines of Andhra Pradesh in the 18th century, the diamond now rests amongst the British Crown Jewels, after passing through several bloodied hands and developing the reputation of bringing ill fate to the men who possessed it. Lore that grew up around its misfortune says that it is meant to be worn only by gods and women. Fifty years after British lawyer Cyril Radcliffe’s midnight drawing of an arbitrary line split the subcontinent in two – an ill-informed cartographic gesture that resulted in large scale violence, mass rape, a mortality toll of 2 million and the displacement of 14 million – both India and Pakistan continue to request the repatriation of this jewel, amongst other stolen artifacts.

Artist Arshia Haq, whose work considers this history and the many centuries of violence that led to its manifestation, centers the embodiment of mourning as a way to reconstruct her and her collective relationship to pain, loss, and violence. Women, in particular, were brutally objectified in the pursuit and desire for nationalism upon colonialism. Anthropologist Veena Das writes that, “the violence of the Partition was about inscribing desires on the bodies of women in a manner that we have not yet understood. In the mythic imagination in India, victory or defeat in war was ultimately inscribed on the bodies of women.” Haq harnesses the affect of this historical trauma and creates a room for reflection. The result is a haunting installation, The Second Coming of Fatima, that speaks to the complex interplay between the validation and erasure of women, specifically within the context of conflict. Fatima, the only daughter of the prophet Muhammad, is an iconic figure in the Muslim female pantheon, and is often invoked in prayers of protection and healing. In a room covered with earth lies an arsenal of gilded throats, the jewels which are also the vessels of severed or silenced speech. Sitting on pedestals, the pieces are fragments of the violated body worthy of reverence, an homage to the physical costs of the colonial acquisition and appropriation of women’s jewelry, wealth, and worth in the Indian subcontinent. Acquisition, on an intimate and institutional level, is explored here through the lack of repatriation of collection objects in Western museums and the violation of female intimacy, rites, and rights.

A sound piece made in collaboration with artist Nour Mobarak merges a sonic rendition of the above Urdu poem with field sounds, from bird songs of the Deccan plateau to news broadcasts as well as more guttural evocations. Haq’s installation pays homage to historical, religious, and mythical female characters, through which she gives form to the amorphous and nebulous process of mourning. Loss erupts from within the earthen soil, and grieving those sacrificed becomes a release, a catharsis that seeks to heal. As Das writes, “could that which died be named, acknowledged, and mourned?”